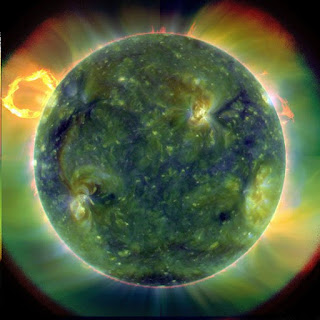

After five years of surprising quiet, the sun roared to life in 2011. Our star erupted with numerous strong flares and waves of charged particles. Many researchers predict the surge will culminate in a peak in the sun's 11-year activity cycle in 2013.

|

Eruptive prominence blasting away from sun |

This year also marked several key advances in scientists' understanding of the dynamics driving our favorite star. Having been relatively quiet since 2005, the sun spouted off a number of powerful flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) this year. CMEs are made up of massive clouds of plasma that are sent streaking through space in any direction at several million mph. When these clouds are aimed at Earth, they can spawn geomagnetic storms that wreak havoc with GPS signals, radio communications and power grids.

"We are getting more CMEs and starting to get some more-energetic CME/flare combinations," Terry Kucera, deputy project scientist with NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory spacecraft, told SPACE.com via email.

Scientists classify strong solar flares in three categories: C, M and X, with the X-class being the most powerful. So far in 2011, eight X-class flares have been observed. The largest solar flare in more than four years exploded from the sun in August. The blast wasn't directed at Earth, instead jettisoning into space.

|

Giant sun spot activity |

Similarly, around Labor Day in September, the sun erupted with several CMEs and solar flares, including an X-class outburst Sept. 6. But Kucera said her favorite eruption occurred on June 7: a medium-size solar flare, a minor radiation storm and a unique CME from an active sunspot region.

"A lot of cool, dense material didn't make it out and fell back to the sun," she said.

The spectacle of plasma crashing backing into our star had never been seen before. "It was amazing to look at," Kucera said. C. Alex Young, senior support scientist with SOHO and NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), agreed, calling it "the top natural event" of 2011. "More than likely, such an event has occurred, but never before would we have seen it in such detail," he told SPACE.com by email.All of these active eruptions are considered normal for this level of solar activity. "During solar minimum, there is an average of one CME every five days, and during solar maximum the average is around three per day," Young said.

|

Eruptive prominence blasting away from the sun |

A number of comets crashed into the sun in 2011, and on July 6 scientists captured one such death dive in its entirety for the first time ever. The observations, made by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory spacecraft, should improve scientists' understanding of comet composition, researchers have said.

Sometimes daredevil comets survive their ordeals against all odds. In December, Comet Lovejoy had a close encounter with the sun that experts thought would be fatal. It passed within 87,000 miles (140,000 kilometers) of the solar surface — but re-emerged on the sun's other side and zipped off into space.

Lovejoy is part of a group known as Kreutz sungrazers. Most of these comets are thought to come from a single giant comet that broke apart several centuries ago. They are named for the 19th-century German astronomer Heinrich Kreutz, who first showed that such comets are related. "Seeing a comet enter the million degree solar corona with an extreme-ultraviolate imager (SDO), then to see one enter and exit is so cool!" Young said.

|

Sun's coronal holes in an x-ray image |

The year also brought a greater understanding of what's happening on the sun. At the start of the year, NASA's twin Stereo probes took up their positions on the side of the sun farthest from Earth, allowing solar scientists to view that previously hidden surface. "This is fantastic," Young said. "With SOHO, SDO, and Stereo, we really see the sun with a completeness like never before." Solar researchers now have their eyes on the entire star, meaning it will have a harder time surprising us. Scientists can identify active sunspots, which may birth intense flares and potentially damaging CMEs, on the "back" side of the sun before they rotate around to face Earth. In January, astronomers reported using the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) spacecraft and the Japanese satellite Hinode to image and measure giant plumes of gas zooming up from the sun's surface. Known as spicules, these fountains were found to be hotter than previously observed, which means they could be a significant cause of the heating of the sun's outer atmosphere, or corona.

Images of 191 solar flares by SDO also helped a separate group of astronomers make some new inferences about the sun. Many of the images showed a delayed brightening, or a "late phase," minutes to hours after the peak. Because they were not connected with another X-ray burst, these late phases had managed to escape scientists' notice in the past. Analysis of a year's worth of images revealed that solar flares generally release more energy than was realized. The solar activity is likely to continue increasing until 2013 or so, Kucera said.Young agrees. "With the increased activity and the great data we have from SDO, Stereo, SOHO, and more, 2012 should be a very exciting year in solar physics."

No comments:

Post a Comment